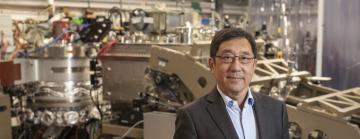

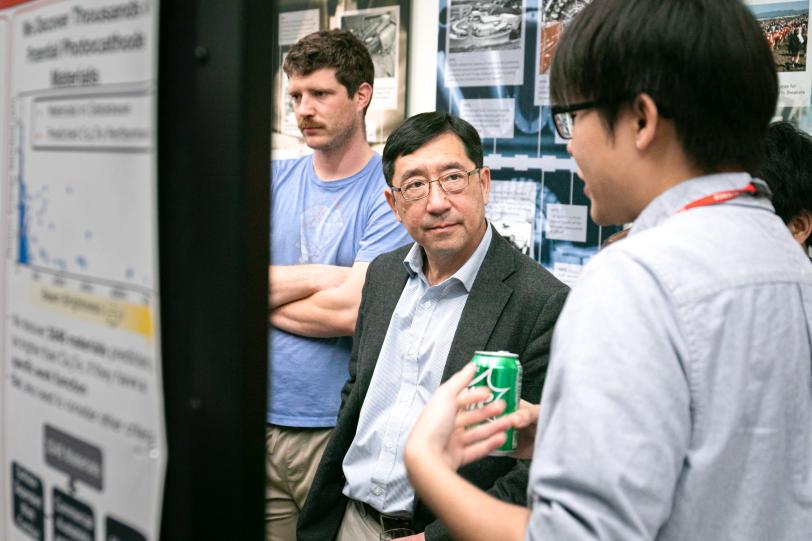

Lab Director Chi-Chang Kao reflects on the past decade as SLAC celebrates 60th anniversary

Under his leadership, the lab diversified its research portfolio, expanded its science impact, advanced major projects, increased collaboration with Stanford and met the challenges of a global pandemic.

By Glennda Chui

Chi-Chang Kao, a noted X-ray scientist and director of the U.S. Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, recently announced that he will step down and return to research. We asked him to look back on his decade as director – which happens to coincide with the lab’s sixth decade of existence.

You became SLAC’s fifth director in 2012 as the laboratory was celebrating its 50th anniversary. What was happening at the lab back then?

I had come to the lab two years earlier from Brookhaven National Laboratory to lead the lab’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL). It was an exciting time. SLAC was going through a major transformation under then-Director Persis Drell from being a particle physics lab to a multi-program lab, and building the tools we would need to carry out that wide range of programs was well underway. And like other DOE national labs, SLAC was looking for ways to use our unique skills and facilities to tackle grand scientific challenges facing the nation and the world.

The Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) – the world’s first hard X-ray free-electron laser – had turned on in 2009. It was an amazing feat – and a tribute to decades of work by physicists, engineers and the SLAC staff – that it worked beautifully from the first day.

Lab DirectorSLAC’s people are the heart of the lab, and every day they demonstrate our core values of excellence, respect, collaboration, creativity and integrity in the work they do and their relationships with each other.

And of course SLAC was still heavily involved in particle physics as well as in astrophysics and cosmology. For instance, SLAC researchers helped develop technology for the ATLAS experiment at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, which joined the CMS experiment in announcing the first observation of the Higgs boson in July 2012. Today our ATLAS group is making major technical contributions to the ATLAS detector upgrade.

So when I was offered the opportunity to be lab director, I thought about what I could contribute to this amazing institution.

Just as the startup of SSRL in the 1970s set a course for X-ray science for decades and even still today, LCLS is another historic opportunity to set the direction of X-ray science, and many other areas of science, for the coming decades. I thought about how I could help shape the future of free-electron laser science.

And it was also clear to me that our connection with Stanford is very important. Stanford operates SLAC for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. The relationship goes right back to our founding. The lab sits on Stanford land, our people are Stanford employees and our faculty teach and mentor Stanford students, many of whom come to the lab for hands-on training. The more we can bring SLAC and Stanford together, the more impact we can have both in discovery science and in research that affects everyday life.

As I took over as director in November 2012, I set out with those two things in mind.

The past decade has been notable for the number of projects and facilities that have come online or are in the final stages of development.

That’s right. They’re the result of many years of work by SLAC researchers and our collaborators in the U.S. and abroad.

One of those flagship projects is a $1 billion expansion of LCLS called LCLS-II, which was considered so critical that DOE gave it mission-need approval just a few months after LCLS opened. We started clearing out one-third of the SLAC linear accelerator in 2016 to accommodate a superconducting linear accelerator that will operate alongside the original copper linac at the heart of LCLS, allowing the facility to produce a million X-ray laser pulses per second. LCLS-II is scheduled to start up next year, and another upgrade that will push the X-ray laser beam to even higher energies is already underway. Those projects have benefited tremendously from high-energy physics investments in superconducting technology development for particle accelerators and other projects.

In addition to the accelerator upgrade, a new suite of instruments was built to take advantage of the high repetition rate of LCLS-II. We’re also preparing to add two state-of-the-art lasers – including a petawatt laser that’s one of the most powerful on the planet, generating a million billion watts – to create extreme states of matter for the study of hot, dense plasmas, astrophysics and planetary science at LCLS-II.

Furthermore, to take full advantage of LCLS-II’s high repetition rate we have also made significant progress in developing advanced X-ray detectors that have very high shutter speeds and are intelligent enough to decide which data to keep and what not to keep, so they can winnow down the amount of data that will be sent down the line for analysis.

In high-energy physics, SLAC’s flagship project is the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which sits on a mountaintop in Chile. It will conduct a 10-year sweep of the Southern sky known as the Legacy Survey of Space and Time – the widest, fastest and deepest survey of the night sky ever conducted – and we expect it to advance our knowledge of dark matter, dark energy, galaxy formation and potentially hazardous asteroids.

SLAC’s contribution to the observatory is the LSST Camera – the world’s largest digital camera for ground-based astronomy. We started building it in 2015, and it’s almost ready for shipment and integration into the observatory’s telescope. We will also host the observatory’s U.S. data facility, which will support data analysis for thousands of scientists around the world.

In particle physics, SLAC is involved in the next-generation search for dark matter particles across a wide range of possible masses. We’re the lead lab for the SuperCDMS-SNOLAB experiment and also play a major role in the LUX-ZEPLIN experiment, LZ, both of which will lie in wait for dark matter particles with detectors sheltered deep underground. On a smaller scale, our researchers are working on the development of Dark Matter Radio, which would tune in signals from dark matter particles called axions in much the same way you would tune in an AM radio signal, and the proposed Light Dark Matter Experiment, which would use spare electrons from LCLS-II to produce dark matter in the lab.

Accelerator R&D has always been an important area of research for SLAC. Just before I became director of SLAC, the Facility for Advanced Accelerator Experimental Tests (FACET) was opened. It’s the third of our DOE Office of Science user facilities alongside SSRL and LCLS, and the only facility in the world that provides high-energy beams of electrons for testing next-generation technologies that could make future accelerators smaller and more capable. It reopened two years ago as FACET-II after an upgrade that opens new opportunities for all our facilities and research programs, from light sources and particle physics to materials, biological and energy sciences.

How has the lab’s connection with Stanford University figured into all of this?

When I became director in 2012, SLAC was already operating four joint institutes and centers with Stanford in the areas of cosmology and astrophysics, materials and energy science, catalysis and ultrafast science.

In 2018 we opened another joint effort, the Stanford-SLAC Cryo-EM facilities, one of the world’s foremost centers for cryogenic electron microscopy research, technology development and training, which complements our bioimaging efforts at LCLS and SSRL. There are now nine advanced instruments on the SLAC and Stanford campuses, and two National Institutes of Health centers at SLAC make cryo-EM available to researchers across the country and train them in how to use it. The center has already made major improvements in the resolution of single-molecule imaging and tomography, and has contributed to our understanding of COVID along with our X-ray facilities.

We have also collaborated with Stanford in several emerging technology areas, including quantum information science (QIS), microelectronics, synthetic biology and artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML). For example, Stanford and SLAC are building a unique Detector Microfabrication Facility that will be a foundry for producing superconducting quantum devices. We’ll also be able use it to develop quantum sensors for the CMB-4 experiment, which will deploy 21 telescopes containing half a million of these sensors to search for ripples in the Cosmic Microwave Background left by the burst of rapid inflation that followed the Big Bang. This is very important for understanding the origin of the universe.

We’re also on track to increase our research collaborations with Stanford on sustainability through the new Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability, building on our decade-long collaborations on energy storage, biosciences and environmental research at SSRL.

It would be hard to overstate the impact that Stanford has had on SLAC research, operations and facilities. In addition to their many investments in SLAC over our first half century, in the past decade the university and its donors have funded construction of the Arrillaga Science Center and one of its key facilities, the Detector Microfabrication Facility, which I mentioned before. And we continue to share many core services with Stanford, such our scientific computing facility, occupational health, payroll and human resources. This allows us to streamline our operations and save money.

Our relationship with Stanford has only grown stronger over the years, providing the combined intellectual power, opportunities for cross-cutting research and access to state-of-the-art facilities that are so crucial to advancing science on both campuses.

What’s next?

These are exciting times, and challenging times too. The lab and its research impact are growing, we have ambitious, creative people and there are a lot of things happening at once.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought both disruption and innovation. We had to make sure our people were safe while delivering on our mission and keeping facilities running. We shifted some of our focus to conduct research that could help advance understanding of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. We were already conducting remote experiments at our major facilities, and we beefed up those capabilities to accommodate more researchers at a distance. We also added virtual events – tours, public lectures and employee activities – to stay connected with each other and with the public. While we have brought back in-person work and events, we are still adapting to a hybrid model of collaboration across the board.

More than a decade after the opening of LCLS we are still just starting to explore all the things that free-electron lasers can be used for, and there are so many exciting directions to pursue –from making and studying matter in extreme conditions to observing chemistry in action, pushing the time resolution of experiments into the attosecond range and understanding how electrons form condensates that give rise to unusual properties in quantum materials. LCLS-II will allow us to probe deeper into all of those areas, and this is what I hope to work on when I return to doing research.

We also look forward to exciting discoveries from the projects that are about to come online, such as the searches for dark energy and dark matter, and from our continuing programs in bioimaging, energy sciences and technology innovation, among many others.

There are many more ideas coming in from the high-energy physics side. In the next year or two, when the new Particle Physics Project Prioritization Panel charts out the next round of strategies, I’m sure there will be other things that SLAC will become involved in.

SLAC’s people are the heart of the lab, and every day they demonstrate our core values of excellence, respect, collaboration, creativity and integrity in the work they do and their relationships with each other.

As I told them in October when I announced my decision to step down, they should all be very proud of what we have accomplished together by coming in every day believing in what we do. The lab’s future is in their hands.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.